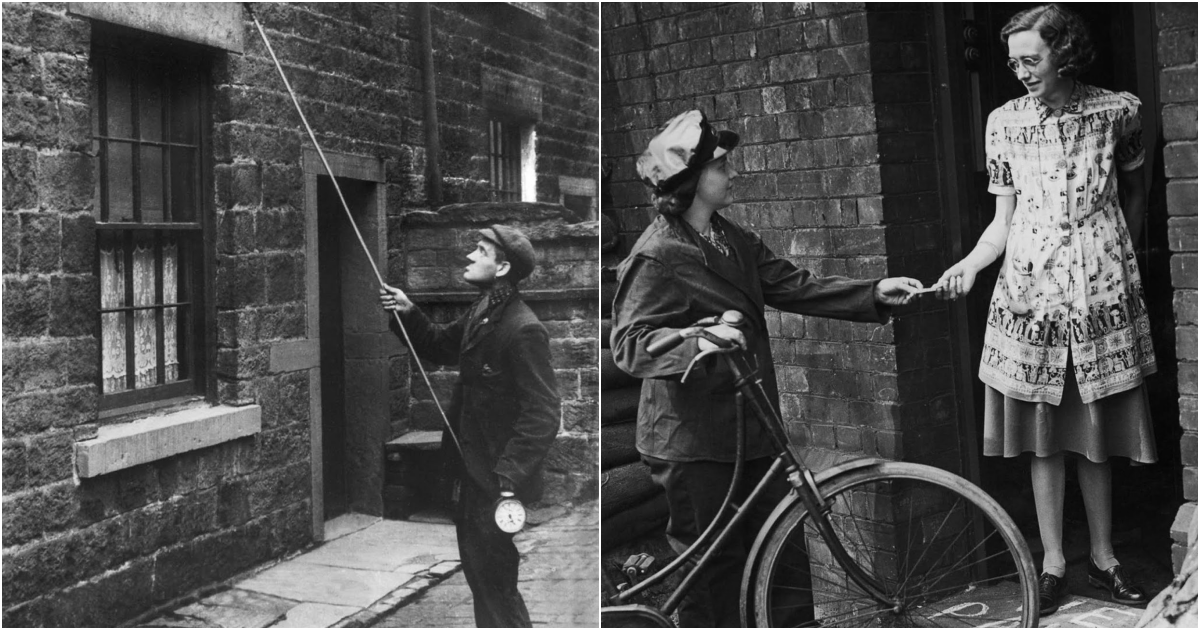

A knocker-up rouses a client in Lancashire. c. 1900.

The knocker-upper profession started during and lasted well into the Industrial Revolution when alarm clocks were neither cheap nor reliable. A knocker-up’s job was to rouse sleeping people so they could get to work on time.

They would be paid a few pence a week to make the rounds and rouse workers, banging on their doors with a short stick or rapping on upper windows with a long pole. The knocker-up would not move on until he received confirmation that his drowsy client was up and moving.

There were large numbers of people carrying out the job, especially in larger industrial towns such as Manchester. Generally, the job was done by elderly men and women but sometimes police constables supplemented their pay by performing the task during early morning patrols.

In Ferryhill, County Durham, miner’s houses had slate boards set into their outside walls onto which the miners would write their shift details in chalk so that the colliery-employed knocker-up could wake them at the correct time. These boards were known as “knocky-up boards” or “wake-up slates”.

Mrs. Molly Moore (daughter of Mrs. Mary Smith, also a knocker-up and the protagonist of a children’s picture book by Andrea U’Ren called Mary Smith) claims to have been the last knocker-up to have been employed as such. Both Mary Smith and Molly Moore used a long rubber tube as a peashooter, to shoot dried peas at their client’s windows.

The “knocker upper” was a common sight in Britain, particularly in the northern mill towns, where people worked shifts, or in London where dockers kept unusual hours, ruled as they were by the inconstant tides.

While the standard implement was a long fishing rod-like stick, other methods were employed, such as soft hammers, rattles and even pea shooters. c. 1915.

Charles Nelson of East London worked as a knocker-up for 25 years. He woke up early morning workers such as doctors, market traders and drivers. 1929.

Doris Weigand, Britain’s first railway knocker-up, makes a call. She is employed to inform workers when they are needed for a shift on short notice. 1941.

Mary Smith earned sixpence a week shooting dried peas at sleeping workers’ windows in East London in the 1930s. (Photo credit: John Topham / TopFoto).

A knocker-up rouses a client in Lancashire. c. 1900.

The knocker-upper profession started during and lasted well into the Industrial Revolution when alarm clocks were neither cheap nor reliable. A knocker-up’s job was to rouse sleeping people so they could get to work on time.

They would be paid a few pence a week to make the rounds and rouse workers, banging on their doors with a short stick or rapping on upper windows with a long pole. The knocker-up would not move on until he received confirmation that his drowsy client was up and moving.

There were large numbers of people carrying out the job, especially in larger industrial towns such as Manchester. Generally, the job was done by elderly men and women but sometimes police constables supplemented their pay by performing the task during early morning patrols.

In Ferryhill, County Durham, miner’s houses had slate boards set into their outside walls onto which the miners would write their shift details in chalk so that the colliery-employed knocker-up could wake them at the correct time. These boards were known as “knocky-up boards” or “wake-up slates”.

Mrs. Molly Moore (daughter of Mrs. Mary Smith, also a knocker-up and the protagonist of a children’s picture book by Andrea U’Ren called Mary Smith) claims to have been the last knocker-up to have been employed as such. Both Mary Smith and Molly Moore used a long rubber tube as a peashooter, to shoot dried peas at their client’s windows.

The “knocker upper” was a common sight in Britain, particularly in the northern mill towns, where people worked shifts, or in London where dockers kept unusual hours, ruled as they were by the inconstant tides.

While the standard implement was a long fishing rod-like stick, other methods were employed, such as soft hammers, rattles and even pea shooters. c. 1915.

Charles Nelson of East London worked as a knocker-up for 25 years. He woke up early morning workers such as doctors, market traders and drivers. 1929.

Doris Weigand, Britain’s first railway knocker-up, makes a call. She is employed to inform workers when they are needed for a shift on short notice. 1941.

Mary Smith earned sixpence a week shooting dried peas at sleeping workers’ windows in East London in the 1930s. (Photo credit: John Topham / TopFoto).